Drowned Animals, Runaway Waste on North Carolina Farms in Matthew’s Wake

As record floodwaters recede, the state surveys the hurricane’s damage to livestock and their waste. Environmentalists weigh in.

By CHRISTINA COOKE

Civil Eats

October 18, 2016

Find the original story here.

With its almost 10 million hogs and 148 million chickens, North Carolina holds some of the highest concentrations of factory farms in the United States. So when Hurricane Matthew dumped more than 15 inches of rain and set off historic flooding in the parts of the state most densely populated by livestock, it created problems—for the farm operations themselves and for the land and people nearby.

While floodwaters have begun to retreat in North Carolina, evacuation orders remain in place in coastal cities like Lumberton, Princeville, Kinston, and Goldsboro, and experts expect rivers to remain in flood stage until early next week.

In eastern North Carolina, swine enterprises—known as confined animal feeding operations, or CAFOs—house an average of more than 4,000 animals each in warehouse-like barns. As of yesterday, the state reported that 1,300 hogs and almost 2 million birds, mostly broiler chickens, had drowned when the buildings holding them filled with water.

“That number could still go up,” said Brian Long, director of public affairs for the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Affairs (NCDACS). “We won’t know until the waters recede.” (Others estimate 5 million birds have died.)

While chicken CAFOs store the birds’ dry waste in piles, hog CAFOs store the animals’ wet waste in giant, open-air pits that take on a pink color from the colonizing bacteria. Each year in North Carolina, hogs produce 10 billion gallons of feces and urine, enough to fill 15,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools, according to a report by the Environmental Working Group in June. When extreme flooding occurs, not only do the animals risk drowning, but the waste lagoons face the potential of breaching (when the walls give way) or being inundated with water.

So far, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ) has not received any reports of breaches or overtopping of hog lagoons, according to Stephanie Hawco, the department’s deputy secretary for public affairs.

“We have received reports of 11 lagoons being inundated by flood water as a result of record rainfall,” Hawco says. But because inundation occurs when outside water comes into the lagoon, she adds, the waste stays put and simply becomes diluted.

An Environmentalist’s View from the Air

Rick Dove, a founder and senior advisor of the Waterkeeper Alliance, a national nonprofit dedicated to preserving and protecting waterways, sees the storm’s effects as much more worrisome than state representatives do.

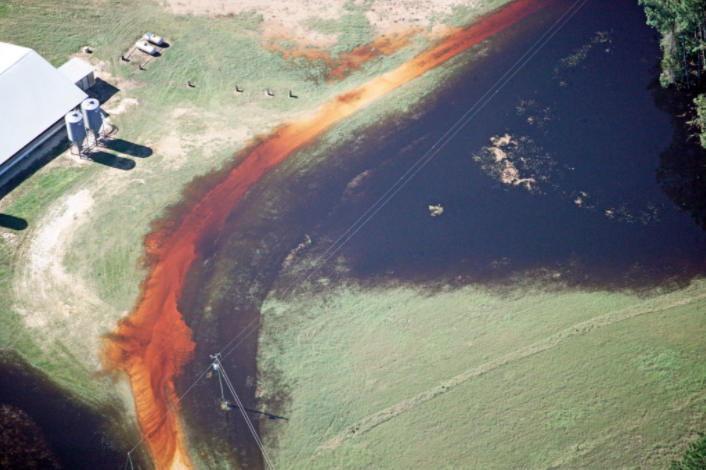

Dove has spent more than 30 hours in the last week flying over the hurricane-ravaged region in a single-engine plane photographing flooded CAFOs from above. “The poultry are getting hit harder than the swine in this hurricane,” he says. “What I’m seeing is a lot of poultry barns that are completely submerged, which means all the chickens inside are dead,” he says. “The number of dead chickens is going to be in the many millions.” Additionally, the floodwaters are washing piled poultry waste downstream, he says.

Dove has also seen at least 15 hog waste lagoons, almost all along the Neuse River, damaged by floodwaters—some inundated, some breached, he says. “The cesspools went underwater—some so far underwater I couldn’t even see them from the air—and the only way I knew there were lagoons there is from when I had seen them before,” he says. Dove confirmed their locations using Google Earth back at his office.

Because hog waste lagoons contain elevated levels of ammonia and nitrates and are often contaminated with fecal bacteria including E. coli and Enterococcus, their contents represent a threat to both human and environmental health. Maps of the North Carolina’s CAFOs released this spring demonstrate that by far, the highest density of CAFOs exist near low-income communities of color.

Wilson County resident Don Webb owned a hog farm back in the 1970s, but shut it down after his neighbors complained that the stench was unbearable. He has since fought the industry’s harmful practices, like the use of the waste lagoons and sprayfields. “Most of these hog operations were earmarked for African American communities, because they were the point of least resistance,” he says. “How many country clubs in North Carolina have got a hog operation causing them a problem?”

Contrary to state and industry claims, Dove says, fecal matter has escaped the confines of the lagoons and is making its way across the coastal plains. A number of lagoons have taken on the color of the surrounding floodwaters since the storm, he says, their former pink color washed off downstream.

Additionally, a ribbon of pink now exists within the main current of the Neuse River. (The Waterkeeper Alliance will release photographic evidence in coming days, he says.) “The industry can put as much spin on it as they want, but they can’t change the truth,” Dove says.

While hurricanes are normally nature’s way of flushing out and renewing coastal areas, Dove continues, “things nature never intended to come down the river are coming down the river.” And when oil, pesticides, and animal waste move downstream and settle out in places like the lower Neuse River and Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds, the toxins cause contamination, and the excessive nutrients lead to explosive algae growth. This growth, in turn, decreases the amount of dissolved oxygen in the water and prompts fish kills, or excessive numbers of dead fish.

“There’s terrible devastation in North Carolina and terrible human suffering, and we should always put that first,” Dove says. “But the health consequences we’re going to suffer and the degradation to our waters will be with us for decades.”

Cleaning Up the Damage

The damage from Hurricane Matthew to industrial farms has so far not been as severe as Hurricane Floyd, which hit North Carolina in September of 1999 and wreaked havoc on the industrial farms and surrounding landscape. That storm killed more than 2 million chickens, turkeys, and livestock—residents remember animal carcasses floating in the floodwaters—and urine and feces leaked into nearby rivers and the groundwater.

In preparation for Hurricane Matthew, some hog farmers moved their animals to higher ground owned by other contractors for the same parent company, says Jennifer Kendrick, public information officer with the NCDACS. Additionally, DEQ field staff worked with farmers to help them lower the level of waste in their lagoons, says Hawco. “Some farms, for example, were pumping and hauling away waste to help reduce the levels in their lagoons,” Hawco says.

Moving forward, the state will collect water samples to test water quality and oversee the dead hogs’ disposal at landfills that are permitted to accept animal mortalities, Hawco says. “We don’t want a repeat of what happened after Hurricane Floyd when animals were buried, which poses a much greater risk to the environment than composting or disposal in permitted landfills.”

To deal with the chicken remains, the state received a $6 million grant from FEMA to purchase carbon material, mostly recycled wood chips, for composting purposes. As of yesterday morning, the state had delivered 58 truckloads of the material to five farms. A total of 12 farms requested the material, but truck access to some was still difficult.

State inspectors plan to increase field visits to farms as road conditions allow, says Hawco. “We are cautiously optimistic that we will not experience the catastrophic damage we saw during Hurricane Floyd,” she says.

Meanwhile, Dove plans to continue monitoring the factory operations from the air as they begin the carcass disposal process. He believes the level of state oversight is insufficient and does not trust the industry to play by the rules. “Why do we even need to be doing what we’re doing as Waterkeepers?” Dove says. “Why isn’t the state doing this? They say they’re up there flying, but I haven’t seen them.”

Photographs courtesy of the Waterkeeper Alliance.