Among Canadians, the fireplace channel seems to rank right up there with ice hockey and poutine in popularity. During our three-day stay in Vancouver BC, my sister, friend and I saw no less than half a dozen crackling fires on television. *

Among Canadians, the fireplace channel seems to rank right up there with ice hockey and poutine in popularity. During our three-day stay in Vancouver BC, my sister, friend and I saw no less than half a dozen crackling fires on television. *

Though you might not guess it, televised fires have an extremely detrimental effect on conversation. Before we noticed the fire on the TV high in the back corner of The Ascot Lounge, a “handsome” new bar on West Pender by our hostel, we’d had a lot to talk about as we sipped red wine. But as soon as we caught sight of the pixelated burning, our conversation ceased, and we all stared slack-jawed at the screen, mesmerized by the crackling and flicking flames and the flannel-clad arm that periodically appeared to shift the logs with a poker, sending red-hot embers spiraling up the chimney.

* Disclaimer: None of us have cable, so this may be a “thing” we're just not aware of. I’d rather attribute it to Canadian genius, and the fact that it just makes sense in this part of the world, where it gets pretty chilly and starts getting dark at 3:30 p.m. during winter.

When we weren’t enthralled by fires on TV, we did manage to get out and see the western coastal city, the third largest in Canada (behind Toronto and Montreal).

Gastown, the city's oldest neighborhood, in the rain. It rained a lot during our visit.

Gastown, the city's oldest neighborhood, in the rain. It rained a lot during our visit.

The steam-powered clock at the corner of Cambie and Hastings streets

The steam-powered clock at the corner of Cambie and Hastings streets

Some highlights:

- The waiter at a cafe on a busy street in the west end spilled the pitcher of soy creamer all over our table and my sister (who fortunately, was still wearing her raincoat). After he wiped up the creamer with a rag, he knocked over the half and half.

- We entered Vancouver, BC with the hypothesis that all Canadians are just plain nice, based on our interactions with our Canadian friend Luke and the Canadian vinyl siding salesman we sat next to on an airplane recently. As we rolled into the city and began to seek out our hostel, we watched an 18-year-old in a crosswalk notice a blind person crossing the street from the opposite direction AND TURN AROUND TO LEAD HER BY THE ARM TO SAFETY before running off to wherever he was going. Sold! Our hypothesis was true.

- We ran across a crew of bagpipers making music in the parking garage beneath the Pacific Centre shopping mall where we parked our car at night and found the droning, kilt-clad vision lovely for its incongruity. Then we realized there was a logical explanation: a parade was about to take place outside on the street. It was still cool.

- On the only blue-sky day of the trip, we drove an hour north to Squamish, or “Sḵwx̱wú7mesh snichim” as the aboriginals say (a word that, for obvious reasons, is a lot of fun to try pronouncing). Located at the base of the 2,300-foot granite monolith called Stawamus Chief, the town is paradise according to many climbers I know. Rather than roping up, however, we hiked to the top of The Chief along a 6.8-mile trail, which followed the cascading Shannon River for a mile or so before cutting through the hardwood forest, over wooden staircases and past granite slabs, to the snowy and icy terrain on top.

At the summit (the third of three, we think—although there’s really no way of really knowing), we enjoyed PB&J sandwiches and an expansive view of the Howe Sound, Whistler and the peaks in Garibaldi Provincial Park.

At the summit (the third of three, we think—although there’s really no way of really knowing), we enjoyed PB&J sandwiches and an expansive view of the Howe Sound, Whistler and the peaks in Garibaldi Provincial Park.

We are eternally grateful for the chains that kept us from plummeting to our deaths.

We are eternally grateful for the chains that kept us from plummeting to our deaths.

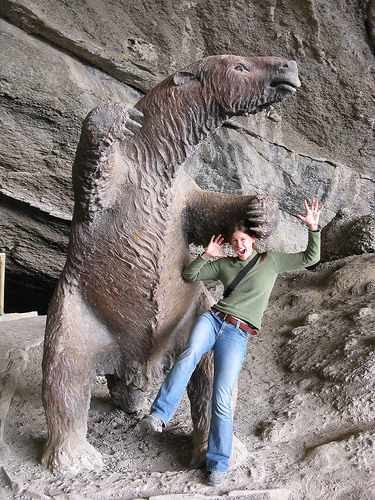

Laura, getting a little crazy by the edge.

Laura, getting a little crazy by the edge.

- Perhaps it was all the physical activity, but we were all blown away by our 4 p.m., post-hike dinner of clam chowder and fish and chips at the Parkside Restaurant, located in downtown Squamish. Best meal of the trip. We liked our waitress too.

- Vancouver’s Chinatown, centered on Pender Street downtown, is one of the largest in North America. After bypassing the open sacks of dried fish bladders and dehydrated geckos (good for asthma when boiled as tea) in one market, I found and purchased two large tins of tea leaves, one jasmine, the other black rose, for only $6. I celebrated my find with a delicious plate of fried rice and sweet and sour chicken at the nearby Jade Dynasty restaurant.

- Our hostel, the St. Clair, offered inexpensive, private rooms furnished by metal-framed bunk beds and not much else. Stark, yes, but clean, inexpensive, centrally located and a good option for travelers on a budget. (I would not, however, recommend The Cambie Hostel a few blocks away. We walked in to the attached and affiliated pubone night and left after 20 minutes of being ignored by the too-cool-for-school waiters who repeatedly walked by our table and chatted with patrons at the bar. Though the atmosphere is funky and comfortable, the poor service just made me mad.)

- As soon as we crossed the Canadian border, our phones sent us text messages telling us they were entering expensive, roaming modes (i.e. going on vacation too), so we shut them off. Being without signal for three days was actually a wonderful break from what’s become normal.

- We sung this a lot, to the tune of “America the Beautiful”: “Oh Caaaanada, oh Caaaanada, from sea to shining seeeeeeeeaaaaaaaaa.”