My parents’ Spanish came a long way during their visit to Chile this month. My mom can now say “Mucho gusto” with a perfect Chilean accent (context isn’t THAT important, is it?), and my dad can get around pretty well with the word “postre” (“dessert”).

During their two weeks here, I introduced them to all the people and places I’ve come to know over the last few months. They met my bosses, friends and self-declared fiances. They hiked to the granite spires that tower over the landscape where I work. They learned to embrace instant coffee and powdered milk with breakfast every morning and become as engrossed in the dramas of the street dogs in town as I am.

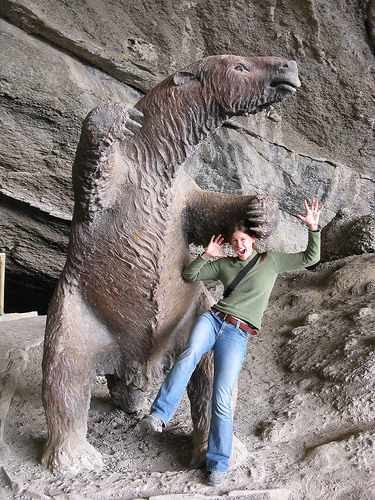

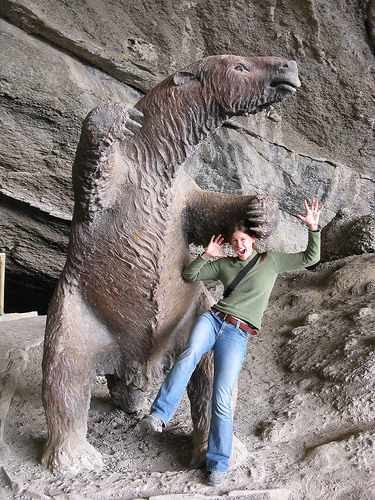

Below is a basic description of how we spent our time together. But before I go any further, let me introduce my parents with some visual aids acquired on the trip.

My dad, Barden:

And my mom, Terri:

W Circuit

Ok, so with the schedule modification, it was more of a transposed U, but same thing. On my parents’ SECOND full day in Chile, we started a super-relaxed, two-hour hike (note the key words) from Lago Pehoe to Campamento Italiano. During this walk, we crossed paths with a Russian language professor from New York who delivered the most interesting 45-minute monologue I’ve ever heard. It seamlessly transitioned from the airplane passing overhead to alcohol abuse in Norway to icebergs, and it was peppered with an informative mix of facts and statistics. We listened, mostly, slackjawed and enraptured.

Also during the hike, my mom caught me up on the wolves new to the Natural Science Center where she works, and my dad filled me in on details from the Hillary/Obama race.

We camped by Río Ascencio and ate pasta and red sauce for dinner. My mom shoveled her food with a titanium spork, which she really likes because its Titanium. I don’t really get it. It burns when it gets hot, and that just doesn’t seem practical for an eating utensil.

We ascended to the mirador at the top of the Valle Frances in the morning. We ran into my friend Chapa, who was guiding a Dutch group over rock and root around the 10-day circuit IN HIS CROCS.

El Tiburon, or Shark's Fin, one of many granite monoliths that surrounds you at the top of Valle Frances.

We stayed in one of the seven cabañas near Refugio Los Cuernos. Down comforters, a skylight, a waterfall right outside. What luxury.

My very-macho guardaparque friends at Campamento Italiano near the base of the towers invited my parents and me into their triangular house for dinner. They even used a teacup to mold the rice into cylinders on our plates. We ascended to the towers in the morning.

My mother conquering the moraine you have to climb to get to the view. This is when I decided a five-hour hike up Valle Silencio that afternoon was not a good idea.

The Cookes (minus one) at the top. (Laura, want to photoshop yourself in?)

ADDED LATER:

I forgot to mention: My sister Laura made it to the towers with us! It was really great to all be together, even if for a short time.

Río Serrano

The morning after finishing the hike, we crammed ourselves and our stuff into neoprene and dry bags, respectively, for a three-day kayaking trip on Río Serrano. The river runs 28-miles along the southern border of Torres del Paine National Park and carries water from six ice fields and many more mountain glaciers to the Pacific Ocean. We paddled from its beginning at Pueblito Serrano to Glaciar Serrano, located right where the river empties into the fjords. (“Fjord,” incidentally, is my new favorite word.)

Our Turkish guides Cem and Serkan both knew pretty much everything there is to know about everything— and were kick-ass cooks to boot.

During our first 45 minutes in the kayak, we faced winds so forceful they blew the river upstream. This is not normal, given that rivers normally flow downstream. I did my best to dig my paddle into the whitecaps and ferry from one shore to the other, all the while getting sprayed in the face with airborne water. Our guides said the wind around here often blows around 50 mph and sometimes reaches around 100. In the United States, that’s considered hurricane force, and it blows houses down. In Chile, you keep paddling.

We decided it best not to run the pounding waterfall in our sea kayaks. Instead, we carried our stuff around.

My father flipped while ferrying across the river at the base of the waterfall. The guides rescued him from the glacial water.

Though we faced strong winds continuously throughout the journey, nothing was on par with our initiation. The river was swift but calm as it wound through lenga forests and beneath dark, imposing mountains. We saw a number of tremendous, age-old glaciers creeping imperceptibly down mountainsides, still at work shaping the landscape.

We ran into virtually nobody else during the whole journey, probably because no roads or trails cut through the Serrano sector of Torres del Paine. We had the whole area — the water, the wind, the glaciers, the forests of lenga trees covered in lichen — to ourselves. I felt privileged.

At one point, we passed several log structures built by a hermit who has not left the river’s bank in the 12 years since he lost a woman to his cousin. I was dying to stop and talk to him, but we continued downstream.

Our last night, we camped by Glaciar Serrano, which measures about 75 feet high at the point it touches the river (that’s the visible part). We kayaked as close as we could to the glacier’s base in the morning.

Otherworldly lichen we ran across in the glacial moraine

We took the 21 de Mayo ferry through the fjords from the end of Río Serrano to Puerto Natales.

A man on the boat wore a plastic bag on his head. I have no idea why. But it fluttered in the wind as he gazed out over the bow, and it was hilarious.

Cueva del Milodon

I almost got eaten by a lifesize replica of the giant ground sloth in the Cueva del Milodon.

In 1895, scientist Otto Nordenskjold discovered the skin of the giant Milodon sloth in a massive cave 25 km north of Puerto Natales. The Milodon, which stood about 20 feet tall, went extinct 8,000 to 10,000 years ago when the roots it gummed for sustenance stopped providing the nutrients it needed for survival.

At the national monument, you can into and around the cave, which measures 656 feet deep, 98 feet high and 262 feet wide and looks a lot like the moon inside. There are a couple other caves you can visit at the monument as well, but we didn’t get to those because the taxi driver who carried us would only wait an hour.

Río Verde

Río Verde basking in the sunlight, Otway Sound in the background

My mom, dad and I ran through the pasture at Río Verde, waving our arms, yelling, and otherwise trying to convince a herd of 100 sheep to take the most direct route between the corral and the green seaside pasture. We were helping my second cousin Christian Santelices (also an international climbing guide) manage the animals on his family’s ranch outside Punta Arenas. The majority of the sheep followed our breathless commands, though eight accidentally separated from their compatriots, got extremely confused and took off for the other side of the pasture. Seeing fleecy butts run off toward the horizon is frustrating, but it’s extremely cute at the same time, so you can’t be too upset.

Most of what we ate during our visit to Río Verde grew up within a mile of our table. The lamb, the lettuce, the eggs: all completely fresh and extremely tasty. Wish I could eat such high quality food all the time. Check out Christian's wife Sue's website on ecogastronomy.

We picked and shelled peas from the family’s garden, then ate them for dinner.

We picked and shelled peas from the family’s garden, then ate them for dinner.

Punta Arenas

The penguins on Isla Magdalena, off the coast of Punta Arenas.

We understood our tour guide to say that the chief predator of the penguin is — get this: the squirrel. As might be expected, this drove my mother and me into uncontrollable hysterics. We misheard, I'm sure, though it would be much more fun if we didn't.

We stopped by the cemetery one afternoon in Punta Arenas to explore the ornately decorated tombs. Macabre, sí, but worth the visit.

To see more photos of our trip, click here.

The salar is 4,633 square miles of packed salt that measures an average of 23 feet thick. It’s what remains of the prehistoric Lago Minchin, which once covered the majority of southwest Bolivia. It’s an illusion-inducing landscape that plays tricks on the mind, and it’s like nothing I’ve ever seen before.

The salar is 4,633 square miles of packed salt that measures an average of 23 feet thick. It’s what remains of the prehistoric Lago Minchin, which once covered the majority of southwest Bolivia. It’s an illusion-inducing landscape that plays tricks on the mind, and it’s like nothing I’ve ever seen before. We discovered people become really small on the Salar de Uyuni

We discovered people become really small on the Salar de Uyuni

And that doing ordinary things becomes much more fun

And that doing ordinary things becomes much more fun  Lago Blanco, with waves frozen in place

Lago Blanco, with waves frozen in place

Flamingos wade knee-deep in many of the lakes, filtering for microorganisms

Flamingos wade knee-deep in many of the lakes, filtering for microorganisms The deserts’ elevation ranges between 12,000 and 15,000 feet above sea level. It’s extremity caused us to become short of breath every time we walked uphill and scramble for hats, gloves and extra layers every time got out of the jeep door to walk around outside.

The deserts’ elevation ranges between 12,000 and 15,000 feet above sea level. It’s extremity caused us to become short of breath every time we walked uphill and scramble for hats, gloves and extra layers every time got out of the jeep door to walk around outside. The rock tree, one of many rock formations we saw along the way

The rock tree, one of many rock formations we saw along the way Simione and another driver operating on our jeep

Simione and another driver operating on our jeep

Laura and me in a tiny town on the edge of the salar, waiting for our drivers to fill the vehicle with gas

Laura and me in a tiny town on the edge of the salar, waiting for our drivers to fill the vehicle with gas